Episode 2:

Developers

As a reminder, it was in 1811 and 1812 that the first rolled zinc roofs were installed in Liège, opening up the way for a potentially profitable application of this new material.

The initiative was taken by a roofer called N.J Doreye. He is the ancestor of zinc roofers!

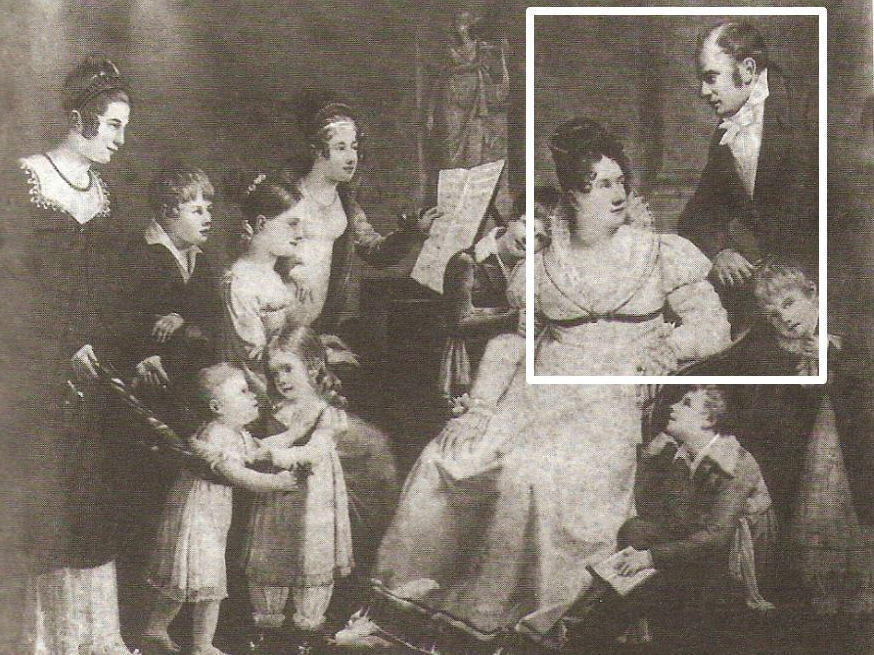

In the first episode, my story stopped at 1813, the year Abbott Dony’s zinc refining patent was purchased by François-Dominique Mosselman. (Photo 1)

Who is Mr Mosselman? The descendent of a wealthy line of Brussels butchers and drapers, who developed the family business in the areas of textile and seed trading, becoming suppliers of the Prussian and subsequently French armies when the Revolution reached Flanders.

A visionary: François-Dominique Mosselman detected a highly promising market!

In 1794, François-Dominique Mosselman opened a banking house in Paris, whose business grew rapidly. He then lived between Brussels and Paris. Between 1813 and 1824, he purchased the first sites for the extraction, production and transformation of zinc, including the mine and the plants in Moresnet, the sites in Hergenrath, Saint-Léonard and Angleur (in the French administrative region of Ourthe) and the coal mines in Foxhall and Darford (in England)

Vieille Montagne zinc was tested for the first time in 1815, on a modest roof in Paris.

It was the same year that Napoleon lost the battle of Waterloo and left office.

Although there was no causal link, this is when zinc started to take off. It was used to cover the curved forms of the “imperial” roofs in the rue de Rivoli in Paris in the early 1820s. (Photo 2)

The roll cap technique developed. Fixing and junction systems were designed for decades to come.

François-Dominique Mosselman had to defend his Vieille Montagne property deeds, especially concerning the site of the very rich Altenberg mine, coveted by the Prussians and the Dutch. As the latter could not come to an agreement, in 1816 they created a neutral territory of several square metres around the mine, the administration of which they left to the site director. I will tell you this incredible story that was to last more than a century!

Then in 1830, Belgium won its independence. It appointed an ambassador to France. A prince called Charles Le Hon.

As luck would have it, he married Françoise “Fanny” Mosselman, the daughter of François-Dominique, our banker-trader.

Duke Charles de Morny: the ambassador of the zinc industry

Honoré de Balzac gave Fanny Mosselman the nickname of “Blue-eyed Iris, the ambassadress with the golden hair”. As charming as she was intelligent and intriguing, she was hostess to the cream of French financial, political and artistic society of the period in their mansion house on the Chaussée d’Antin in Paris (purchased from the banker Récamier in 1805 by her father), which became the Belgian embassy.

In 1832, Alfred Mosselman, Fanny’s brother, took over the family business. He created a sort of holding called “Mosselman brothers and sisters”, in which the Bank of Belgium invested some 800,000 francs in 1838!

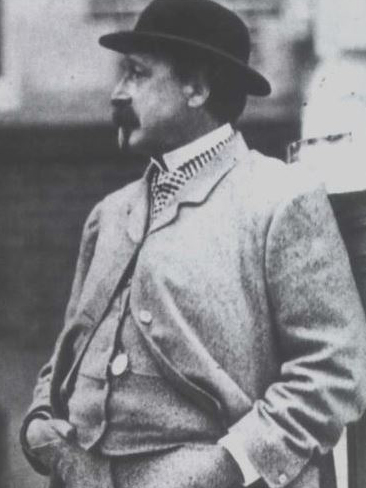

One day in 1833, the Duke de Morny, a brilliant, influential aristocrat who was the illegitimate son of Queen Hortense and General de Flahaut (Talleyrand’s grandson) (Photo 4), was invited to an evening at the Belgian embassy. He immediately fell in love with the beautiful ambassadress, who became his mistress for over twenty-five years!

As an astute businessman, de Morny invested in the rapidly growing sugar industry. To please Fanny, he became an active shareholder of the “Société des Mines et Fonderies de la Vieille Montagne”, which was created in 1837. De Morny was to become the greatest ambassador of the zinc industry. Fanny would finance his irrepressible political rise.

And in 1851, it was this same Duke de Morny who was behind the coup d’état that placed his half brother Napoleon III on the crown. He became the Emperor’s closest advisor.

And so the story of La Vieille Montagne became intertwined with History.