Episode 9:

From the 1970s to the turn of the 21st century

Leading means planning. Even if the worst may never happen, one always has to prepared for hard times. The previous episode of this saga ended at the start of the 1960s. Vieille Montagne had regained its dignity and dynamism after the hardships of the Second World War, and was in marching order to face the future.

Rolled zinc stages a revolution

At the very beginning of the 1970s, the lights on the zinc industry’s control panel were still green but competition was severe in all domains. Technically speaking, methods for rolling zinc were being modernised. The old so-called technology “packets” were gradually being abandoned (*) throughout Europe. The first continuous casting for small thicknesses (700 mm effective thickness) proved satisfactory because they provided an unprecedented level of quality and precision in terms of thickness of sheets and coils. But the market was waiting for larger widths. Industrials needed to propose at least 1,000 effective mm.

So during this decade, the Compagnie Royale Asturienne (CRAM) and Vieille Montagne both decided to invest in the latest generation continuous casting technology (the American Hazelett technologies). These highly automated machines increase production capacity significantly. Another key strength of this technological breakthrough: these infrastructures enabled the sector to make a quantum leap in terms of quality, thanks to the introduction of a new Copper-Titanium alloy (known as Cu-Ti). This alloy (a substitute for the traditional Zinc-Cadmium) improves the formability of rolled zinc while reducing creep - the deformation of zinc due to its own weight which can give roofs a creased appearance after a few dozen years!

This choice of alloy had an unexpected effect. It would gradually change the colour of Paris. Let me explain. With the cadmium alloy, the patina of natural zinc sheets was bluish in colour, a colour that was immortalised by the Impressionists in their paintings (see below painting by Monet). The new Copper-Titanium alloy, with its modest copper content, gives a darker patina. This mouse-grey colour gradually changed the rooftops of the “City of Light”, forming an inimitable monochrome cloak. Those famous 50 shades of grey!

Excess production capacity and collapse of demand: an unprecedented situation!

In 1966, Rheinzink - a new competitor for Vieille Montagne recently founded in Germany - built a high capacity rolling mill.

In France, at the start of the 1970s, the promise of rather over-evaluated growth in the construction market encouraged the main players in the zinc market to make massive investments.

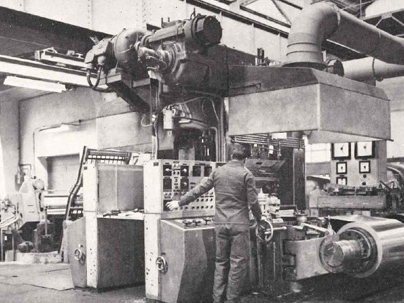

(Photo: Rolling mill in Bray et Lû)

The CRAM made the technological choice of reliability by separating the rolling mill – a classic non-reversible duo (2 rolls) – from the finishing section.

Vieille Montagne, in keeping with its engineering culture, wanted the very best. It opted for a reversible quarto (4 superimposed rolls) capable of rolling up to 0.3 mm thickness (chocolate wrapping as the old saying went!). But the development phase took longer than planned. Word had it that, with a heavy heart, Vieille Montagne had to purchase part of its rolled zinc from its hereditary enemy - CRAM - in 1971!

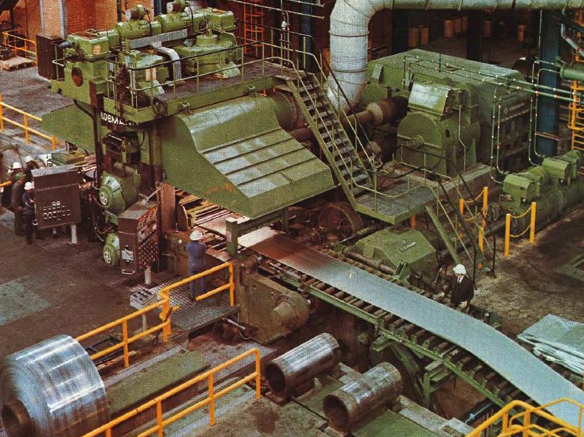

(Photo: Rolling mill in Viviez)

These two modernised rolling mills would be part of Vieille Montagne when it took over CRAM in 1986. They are still working today in 2017 and ensure the entire rolled zinc production of Vieille Montagne, now renamed VMZINC.

In the refining domain, Métallurgie Hoboken-Overpelt, Société Métallurgique de Prayon and Compagnie Royale Asturienne des Mines (CRAM) all inaugurated new zinc electrolysis plants.

Vieille Montagne forged ahead and in 1978 doubled its electrolysis capacity in Balen, increasing it to 200,000 tons thanks to the introduction of large cathodes (°). Again, Vieille Montagne wanted to maintain its technological leadership, which guaranteed its difference and its competitiveness.

(°) From the first cathodes (1.3 m²) we progressed to Jumbo cathodes and then the famous Super Jumbo cathodes, whose surface was almost three times greater (3.2 m²) (See above)

Over a five-year period, Europe was propelled to the cutting edge of technology, with the capacity to produce way more than demand required. Unfortunately, the economy started to change in 1974, with the first petrol crisis. Energy costs soared and were a major drain on the already fragile situation of the highly energy intensive non-ferrous industry! In addition, zinc prices were plummeting due to overcapacity and a drop in demand.

At the start of the 1980s, the Belgian non-ferrous industry was practically on the verge of bankruptcy! It was only a sudden, providential increase in silver prices that enabled Vieille Montagne to survive for a period, as well as the fact that it had been a little less badly affected than others, as its processes facilitated extraction and refining of this precious metal.

This economic downturn had terrible repercussions on the zinc sector. Between 1975 and 1978, for the first time in its history, Vieille Montagne experienced losses (1.3 billion Belgian francs (32 million euros)). This unprecedented crisis sounded the death knell for the Walloon non-ferrous industry. Société Métallurgique de Prayon’s plant (located in my home town!), the furnaces in Flône and the zinc white plant in Valentin-Cocq all stopped work. In France, the rolling mill in Bray was stopped (1978), electrolysis in Viviez was closed in 1985. CRAM went bankrupt and sold most of its assets. A plan to save the French zinc industry was organised in collaboration with the public authorities and the European commission. It was the end of an era.

A series of restructuring

In 1981, Société Générale de Belgique, a shareholder in the majority of companies in the non-ferrous sector in Belgium and France, launched major restructuring of the sector. Firstly, it took over Union Minière and therefore Vieille Montagne, and then transferred its shares in non-ferrous metal companies to a new Union Minière, of which it holds all the shares.

At the end of 1988, French group SUEZ took over Société Générale de Belgique (and therefore Union Minière and its subsidies), under the nose of Italian condottiere Carlo de Benedetti, following an incredible public takeover bid (**).

This change had a determining impact on the future of Vieille Montagne. In 1989, Union Minière, directed by its shareholder SUEZ, took over MHO (Métallurgie-Hoboken-Overpelt ), Vieille Montagne and its engineering company Mechim to become an integrated industrial group with over 16,500 people. Its market capitalisation rose to 65 billion Belgian francs.

Vieille Montagne no longer existed as an independent legal entity. The employees left the historic head office at Angleur and moved to Woluwé St Lambert, in the suburbs of Brussels, to the new Union Minière (UM) head office.

In 1991, Jean Pierre Rodier, the new UM administrator (formerly with Pennaroya), restructured, rationalised and reduced costs. He stopped zinc electrolysis in Overpelt, postponed the new electrolysis extension in Balen and cut overall staff numbers by over 2,000 employees!

Union Minière is structured and regains balance

To better adapt to its markets, Union Minière was organised in twelve autonomous profit centres or “business units”, defined according to the products and services proposed. The idea is to highlight sectors where the company is positioned as world leader (production of Germanium, transformation of Cobalt, complex metallurgy) or as European leader (refining of copper and zinc).

Concentration of the Belgian zinc sector was at last complete, with the creation of the “Zinc Business Unit” comprising all activities of the former Vieille Montagne plants (Balen, Viviez, Calais) that were taken over, Compagnie Royale Asturienne des Mines (Auby), MHO (Overpelt) and Union Zinc (Clarksville -USA). With overall capacity of 520,000 tons, at the start of the 1990s Union Minière controlled almost 10% of world zinc production.

In 1994, after three years in the red, Union Minière finally returned to surplus and decided to become what is known as a “custom smelter”, i.e. a smelter that is not integrated upstream and supplied by the open zinc concentrates market. To reduce its debt, Union Minière sold its last mines, including the famous Ammeberg mine in Sweden, in 1993. A new page was turned. Vieille Montagne building activity survived and was managed separately as it is counter-cyclical. When zinc prices decrease, it maintains the price of its transformed products at levels that make its commodity zinc colleagues jealous! But when prices rise, the building activity has to “weather the storm” and crush its profit margins, thankfully just for short periods as high cycles are less frequent than low cycles! This higher profitability would later lead to the creation of an independent Building Products Business Unit within Umicore.

I would like to share an anecdote with you: during the 1990s, Union Minière’s communication departments advocated for some time to change the brand of the building activity in order to sell its products under the name “Union Minière Bâtiment”, rather than Vieille Montagne – which became VMZINC in 1994. Luckily, we remained steadfast by giving them feedback from zinc roofers who eloquently recounted their attachment to the historic Vieille Montagne brand. Changing the brand would have been a strategic and symbolic mistake!

Down through the years, the DNA of “Vieille” as it was called, was protected and rekindled like the flame of a wood-fire by those working with rolled zinc!

The reconquest strategy

In 1995, the new Chief Executive of Union Minière, Karel Vinck, launched a very determined investment programme to the tune of 22 billion Belgian francs ( 1 € = 40 BF), while maintaining actions aimed at reducing costs. 3,000 more jobs were cut. Numerous activities deemed as non-strategic were put up for sale.

In terms of the zinc building activity, Asturienne Penamet (the roofing products distribution network inherited from CRAM ) was sold in 1998 to the Point P Group. I took part in those negotiations as Commercial Director of VMZINC in France!

Karel Vinck initiated selective geographic expansion of the company, giving priority to emerging markets with high growth potential (Asia, Eastern Europe, USA). However, in 1998, the group yet again had a brush with disaster. Three factors contributed to this new crisis situation. Prices for most non-ferrous metals were decreasing and the dollar collapsed, massively affecting European competitiveness. Above all, the launch of the new “precious metals business unit” foundry in Hoboken experienced severe difficulties (***). I can clearly remember these difficult years during which all of the Group’s Business Units, including ours, were called upon to support it, in particular by postponing all investments sine die!

I can remember that the amount of investments we made in 1998 was no higher than 150,000 French francs, i.e. 25,000 euros, a pittance… but all for a good cause as happily, at the turn of the 21st century, the group’s activity recovered, thanks in particular to a higher than expected rate of return by the famous foundry in Hoboken!

From Union Minière to Umicore: the transmutation

It was Thomas Leysen, a connoisseur of the Group (****) who was appointed as its Chief Executive in 2000, that launched what could be referred to the transmutation of Union Minière group! His credo: develop the company in the area of technologically advanced materials and in recycling of the metals it produces. The famous motto “closing the loop” was adopted and rolled out in the entire organisation. For the new administrator, it was about exceeding the negative image overshadowing Union Minière, that of a basic metals producer, which is no longer the case.

After selling its mines and its primary metals transformation activity, Union Minière focused on the end use of its products. Good news for the zinc building activity, which was proposing high added-value transformed products and already targeting its end clients. At this period, VMZINC was the internal embodiment of a model to copy!

In 2001, Union Minière became Umicore. Its new name came with a strong baseline, “Materials for a better life”, expressing the objectives targeted. The company was a central (Core) player in the materials domain. The products it was developing were the basis for a multitude of applications to facilitate daily life. The first two letters U and M are Union Minière’s initials, in reference to the group’s historic roots.

In 2003, the company deliberately withdrew from activities it considered too cyclical. Firstly, copper refining (creation of the new independent company, Cumerio). Then, in 2007, zinc refining activities (creation of the Nyrstar company in a joint-venture with Australian group Zinifex).

In the year 2003, all that remained in the Umicore Group were the zinc activities considered to have the highest added-value: oxides & dust and the Zinc Chemicals business unit based in Angleur in Belgium; and the Building Products business unit based in Bagnolet on the outskirts of Paris, where I have been working since 1986.

The big deal

It was in 2003 that Umicore made a major acquisition (700 Million €), when it purchased the German group PMG (Precious Metal Group), a subsidiary of American group OMG. It was in fact the former “precious metals” unit of German company Degussa, which in 1887 had intervened financially in the creation of the Hoboken plant! This acquisition gave Umicore a new dimension (an additional 3,800 staff) while accelerating its refocus on the advanced materials sector. The group was now considered by financial markets as a company providing solutions (like the Building Products BU!) rather than a provider of materials, and as a company investing and developing in promising markets.

Promising markets

Marc Grynberg, former financial director and Autocatalyst Business Unit director became chief executive of Umicore in November 2008. His analysis of key societal trends and populations’ expectations clearly positioned sustainable development and environmental protection at the heart of the planet’s preoccupations. He launched two ambitious five-year plans (2010-2015 and 2015-2020) based on these observations.

The skills acquired by Umicore in the area of recycling and energy were strengthened. The existing offer of products shipped in modern vehicles (various types of batteries and autocatalysts in particular) enabled Umicore to position itself firmly in a clean mobility stance.

For the Building Products Business Unit, at the beginning of the 21st century, the environmental dimension of rolled zinc was highlighted for the first time. Production of rolled zinc consumes less energy than that of steel or aluminium. Above all, it is recyclable and has a 96% effective recycling rate in Europe.

So “old rolled zinc”, as it called on work sites, remains valuable when it is removed after eighty or one hundred years of loyal services on roofs - between 50 and 70% of London Metal Exchange (LME) prices! Not one gram ends up in rubble. Roofers know how to sort and store old gutters and roofing panels and sell them when zinc prices rise a little! This is useful and practical as master roofers convert the value of resale into bonuses for their best roofers.

Umicore is continuing its policy of withdrawing from its activities that are deemed less profitable, including the last two zinc business units, which are still industrially closely linked to the basic material they manufacture. The Zinc Chemicals Business Unit was sold in 2016. It has since been renamed Everzinc by its new shareholder.

The same will apply to the Building Products Business Unit, which is currently being sold and will leave the Umicore group before the end of 2017.

Our division is now the sole guardian of the memory of Vieille Montagne, whose initials it has kept in its VMZINC brand.It is interesting to observe that rolled zinc, which in 1811 made up the first application of this new material, remains the last activity to bear this prestigious name 206 years on. And this is no small source of pride for the staff who this year are celebrating the 180th anniversary of Vieille Montagne!

In the last post of this Saga, the tenth and last episode, it is with great enthusiasm that I will tackle the delicate exercise of projecting VMZINC into the future and imagining what our company will be proposing in 2050!

Roger Baltus

Engineer - Architect

VMZINC Communication Director

(*) The last batch production rolling mill was that of the Asturiana das Minas company in Porto, Portugal, built in 1945 and dismantled when it was taken over by Vieille Montagne in 1990. This acquisition made it possible for Vieille Montagne to directly supply its rolled zinc from the Viviez plant, to enter the construction sector in Portugal and become directly involved in the installation of its products via its Portuguese subsidiary’s installation company.

(**) When, on Monday 18 January 1988, Italian financier Carlo De Benedetti announced that he was preparing a public takeover bid for the Société générale de Belgique (SGB), there was talk of an elephant in a china shop, a modern man among dinosaurs!

The Générale de Belgique, also known as the “Old Lady”, with its century and a half of history, was like a financial octopus spreading tentacles to the four corners of the kingdom of Belgium, in the majority of the national economy’s segments.

Among the shareholders, with varying levels of participation, were Générale de Banque (today merged with Fortis), energy company Tractebel (taken over by Suez), Union Minière (which became Umicore), CBR (a cement manufacturer now owned by a German company), shipowner CMB, FN and Arbed (steel industry).

Carlo De Benedetti missed the target. Although not by much. Suez played the white knight. As a result, the Belgian economy suffered greatly and almost turned on its head.

(***) The original techniques used for this new foundry made its development phase very laborious. The objective was to increase added value of processes and profitability by freeing it from supply of high content raw materials. The plant now processes materials with highly diverse origins (sub-products from the group’s other plants, scrap from consumer electronic products (computers and subsequently mobile phones)). This would prove to be a very wise choice that would bring unprecedented success over the coming two decades.

This period was marked by the withdrawal of Société Générale from the non-ferrous sector (from 50.2% to 25.2% in 1997)

(****) He directed Sogem from 1988 to 1994, the Cobalt business unit from 1994 to 1998, the strategy department from 1998 to 1999 and very briefly the Copper and precious metals business group until 2000.