Episode 5:

Social relations

The road to solidarity

Traditionally, Vieille Montagne has always paid great attention to the balance between its white collar workers, blue collar workers and operators! During the 19th century, the pioneering social innovations it implemented were rewarded, notably by an honorary diploma during the 1867 Universal Exposition in Paris.

In episode 4 of this saga, I had already highlighted the “social laboratory” dimension created by this “small country” (ndlr: the neutral territory of Moresnet). I thought it was important to take another look at this specific feature of the company in this episode, because it is part of our DNA. And I can personally confirm that it is still present in current human resource management policies.

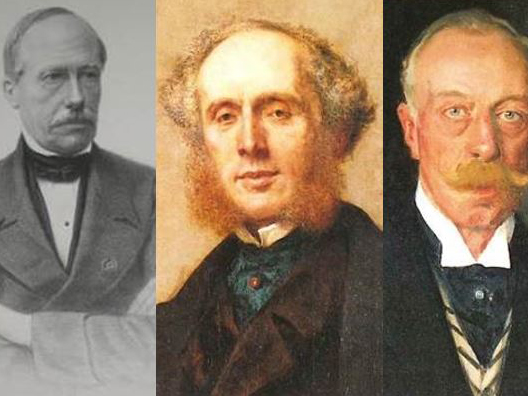

Although we know hardly anything about the social policy led by the first directors, Jean Jacques Dony and subsequently François-Dominique Mosselman, it is certain that Charles de Brouckère, who directed Vieille Montagne from 1841 to 1847, took remarkable initiatives given the context of the first half of the 19th century.

(See below the photos and portraits of Mrs Charles de Brouckère / Louis-Alexandre & Gaston St Paul de Sinçay)

An association between the worker and the entrepreneur

To contribute to the “socialist utopia”, de Brouckère advocated what he called the “association between the worker and the entrepreneur”. On top of their fixed salary, workers at Vieille Montagne were paid bonuses according to their productivity! This modern principle of bonuses for work was applied in the company throughout the 19th century.

De Brouckère also created a savings society for the company’s workers and set up canteens at each plant. His successor, Louis-Alexandre St Paul de Sinçay, continued in the same vein. He developed various provident institutions for the workers: an Emergency Fund, which assisted workers who were ill or injured, and a Pension Fund (fully financed by Vieille Montagne), via which beneficiaries were paid a survivors ‘pension.

Other ground-breaking social progress for the period: workers participated in the management of these various funds via elected representatives.

In 1880, management at Vieille Montagne believed that by showing they cared about their workers, the company would “substitute salutary belief in solidarity (ndlr: between categories of staff – between workers and bosses) the fatal prejudice of antagonism between capital and work.”

A revealing indicator of this successful association between workers and their employer: the company hardly ever experienced strikes. This is illustrated by the fact that Vieille Montagne workers did not participate in the famous general strikes of 1902 and 1913.

Industrial paternalism

Vieille Montagne was not the only company to take this route, which has been described as industrial paternalism. Menier (chocolate manufacturer), Michelin (tyres), Leroy (wallpapers), Godin* (heating stoves), Schneider and Wendel (steel industry) in France, and Solvay (chemicals) in Belgium all practiced it in a similar manner.

(*) Jean-Baptiste André Godin went even further by developing the concept of production cooperatives and by building the famous family residential community called the Familistère de Guise (see above)

What was the dominant idea for these enlightened Christian or liberal businessmen? The idea of taking care of “their” workers so that they would be happy, and even proud, of their company, productive at work and loyal to their employer. Employers often carried out their action based on the model of a job for life, using a generous approach fuelled by the belief that the working classes needed to be trained, supervised, guided and moralised to have the possibility of perhaps one day accessing the coveted status of the middle, higher classes or ruling classes.

Although this form of social control of workers was sometimes denounced (babies were born in the maternity hospital built by the company and people were buried in the cemetery funded, as was the church, by the company), it is nevertheless true that it was the source of much progress in relations between business owners and workers. These new practices and the balance they generated in social relations within these companies served as examples to other employers. They also benefitted the social struggles that took place at the end of the 19th century in the majority of Europe and North America.

However, these “closed” models did not resist the Great Wars or the acceleration of the globalisation process. Above all, it was technical progress, the increase in individual comfort – and more generally an increase in workers’ standard of living during the post-war boom years – that ended this “industrial paternalism” approach.

On the agenda for the next episode of this saga: Vielle Montagne in the turmoil of competitiveness and that of the First World War.